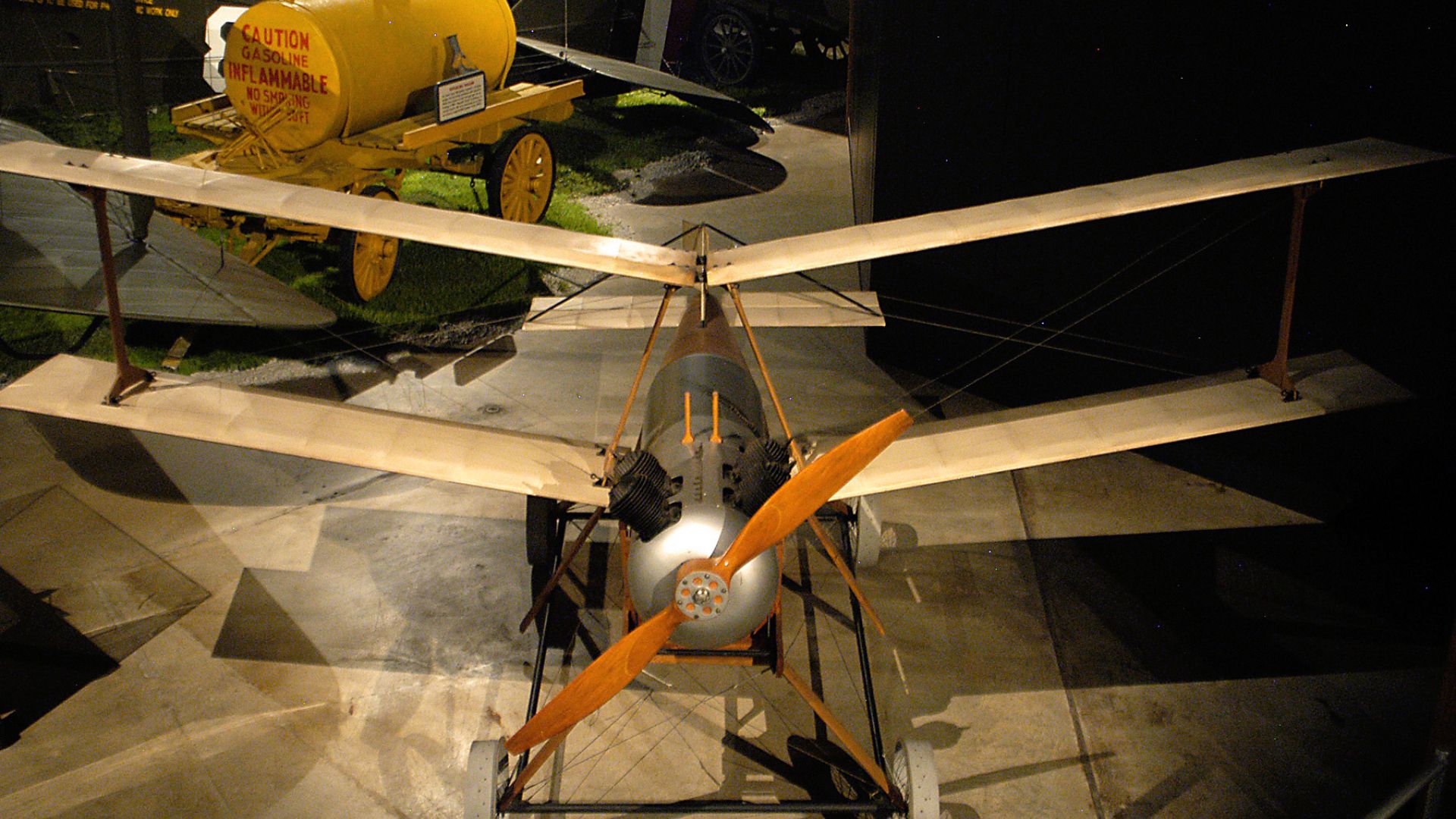

Image via United States Air Force

With the Ukraine War and other modern conflicts, drone warfare has caught the attention of the public for understandable reasons. While the thought of unmanned aircraft piloted by someone far away, maybe even in a different part of the world, can seem like a simultaneously fascinating and scary concept. However, most people don’t realize drones have been around for over a hundred years.

It was the United States which developed the first remotely controllable aircraft for use in World War I. Called the Kettering Bug, there’s some debate about whether or not it constitutes a true drone aircraft or is in fact the early predecessor for the modern cruise missile. We think a valid argument could be made for both, but we’re highlighting how it was in fact the first true drone.

Really, you shouldn’t be surprised that the first drone was used in WWI considering how both sides of the war tried aggressively using military aircraft to dominate the skies. When the US entered the war in its late stages, it didn’t stand a chance in the aerial dogfights dominated by the infamous Red Baron and others.

Instead, the military launched a secretive project headed up by Orville Wright (yes, one of the Wright Brothers) and Charles F. Kettering, an electrical engineer. The two came up with a simple, cheap, yet wonderfully effective craft.

Powered by a simple Ford four-cylinder engine producing just 40-horsepower, the aircraft could cruise without a pilot for up to 75 miles. The Kettering Bug weighed a mere 530 pounds (which included its 180 pound payload) thanks in large part to fuselage being made of paper mâché and wood laminate. It was 12 feet long and had a wingspan of 15 feet. The diminutive size was supposed to make detection by the enemy difficult until it was too late.

Operators had to calculate not only the distance to a target but also wind speed and other environmental factors, somewhat similar to what snipers do before taking long shots. With that information, they would dial in the number of engine revolutions necessary before the wings would break free and the fuselage with a bomb nestled inside would fall, hopefully hitting the predetermined target – ideally a heavily-fortified enemy position which couldn’t be hit by ground troops easily.

The operator had to launch the drone using a dolly on a track, sling shotting it into the air. Funny enough, some drones today are launched in somewhat similar fashion. While they lacked the extreme precision we have grown accustomed to, the Kettering Bugs were advanced technology in 1918.

Sadly, the Kettering Bug never saw combat use as the war ended before they could be proven on the battlefield. However, the idea wasn’t completely abandoned and thus the era of drone warfare had begun.

There was one big flaw about the Kettering Bug: it wouldn’t return at the end of its mission. The United States Air Force didn’t develop drones to leave and return from a mission in one piece, which are more like the modern unmanned aircraft we know today, until the latter part of the 1950s. Still, the Kettering Bug started in motion something Kettering and Wright probably had no idea would one day become reality.

2 thoughts on “The First Drones Were Developed For WWI”